Begin jaren ’70 was er ophef in de media: de Universiteit van Californië in Berkeley discrimineerde bij het toelaten van studenten. De toelatingscijfers van 1973 waren duidelijk:

| Aantal kandidaten | Toegelaten | |

|---|---|---|

| Mannen | 8442 | 44% |

| Vrouwen | 4321 | 35% |

Mannen worden vaker toegelaten dan vrouwen. Met een statistische toets is na te gaan of deze cijfers niet gewoon toeval hadden kunnen zijn. Er zijn verschillende toetsen die geschikt zijn voor dit soort analyses (de een wat geschikter dan de ander), zoals de chi-kwadraat toets (eventueel met continuïteitscorrectie) of de exacte toets van Fisher. Welke geschikte toets je ook neemt, het antwoord is duidelijk: de kans dat deze vrouwonvriendelijke resultaten het gevolg van toeval zijn is verwaarloosbaar klein: kleiner dan 1 op een miljard.

Een rechtzaak volgde vanwege dit overduidelijk geval van discriminatie. Een team van statistici uit Berkeley, onder leiding van Peter Bickel, besloot de data nader te bestuderen. Hun conclusie, beschreven in het paper “Sex Bias in Graduate Admissions: Data from Berkeley” (paywall) in Science, is duidelijk: er is helemaal geen sprake van discriminatie.

Wat was het geval? Vrouwen bleken zich, in het algemeen, aan te melden voor studies waarbij een lager toelatingspercentage gold vergeleken bij de studies die voor mannen populair waren. Zo was er een faculteit (faculteit ‘B’ noemt Wikipedia deze; ik kan de data van Bickel et al zelf ook niet inzien vanwege de paywall) waar bijna twee-derde van de aanmeldingen gehonoreerd werden, terwijl bij een andere faculteit (‘E’) slechts een kwart werd toegelaten. En wat bleek: de toegankelijke faculteit B was veel populairder bij mannen (560 aanmeldingen) dan bij vrouwen (25 aanmeldingen) terwijl de strenge faculteit E twee keer zo veel vrouwen (393 stuks) als mannen (191 stuks) moest beoordelen. Indien rekening gehouden werd met de verschillen in strengheid van de verschillende faculteiten, verdween de discriminatie volledig. (Sterker nog: bij vier van de zes faculteit lag het toelatingspercentage van vrouwen hoger dan dat van mannen).

Dit fenomeen staat bekend als de Simpsonparadox, vernoemd naar de Britse statisticus Edward Simpson die in 1951 een paper getiteld “The Interpretation of Interaction in Contingency Tables” publiceerde (semi-paywall). Dit femomeen is breed bekend.

Tot zo ver de jaren ’70. September 2015 was er ophef in de (sociale) media: NWO discrimineert bij het toekennen van onderzoeksbeurzen. In opdracht van NWO zelf, hebben Leidse psychologen Romy van der Lee en Naomi Ellemers zich verdiept in de door NWO toegekende subsidies van de rondes van het VENI-subsidieschema uit 2010-2012. Hun paper “Gender contributes to personal research funding success in The Netherlands” (paywall, maar het ‘supplementary material’ is dan weer wel gratis) verscheen onlangs in PNAS. De cijfers zijn duidelijk:

| Aantal Beursaanvragen | toegekend | |

|---|---|---|

| Mannen | 1635 | 17,7% |

| Vrouwen | 1188 | 14,9% |

De cijfers zijn wellicht niet zo overduidelijk als die van het voorbeeld uit Berkeley, maar mannen krijgen inderdaad relatief vaker een beurs toegekend. De auteurs zelf schrijven “The success rate was systematically lower for female applicants than for male applicants [14.9% vs. 17.7%; χ2(1) = 4.01, P = 0.045, Cramer’s V = 0.04]”. De p-waarde zit nèt onder de magische 5%-grens, dus het is significant, dus het is bewezen: NWO discrimineert! Althans, dat was de strekking van de krantenkoppen. Maar zo simpel ligt het niet. Op de hier gebruikte methodiek kom ik onderaan deze post nog terug, maar mijn hoofdbezwaar is dat hier ook duidelijk sprake is van de Simpsonparadox.

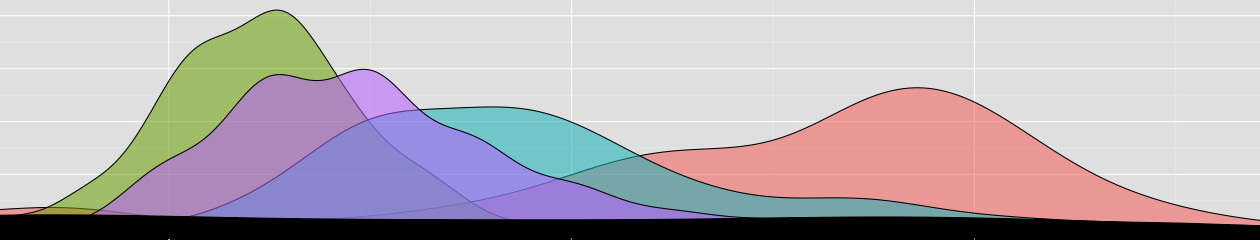

In de online tabel zijn de toekenningspercentages uitgesplitst naar de 9 verschillende onderzoeksprogramma’s van NWO. En wat blijkt: er is zowel een enorm verschil in het aandeel van vrouwen bij de aanvragen per programma (variërend van 11% tot 51%) als een enorm verschil in honoreringskans per programma (variërend van 13% tot 26%):

Het aandeel vrouwelijke aanvragers is het hoogst bij ZonMW (gezondheidswetenschappen) en MaGW (Maatschappij- en Gedragswetenschappen) en dit zijn precies de twee programma’s met de slechtste honoreringskans. Het aandeel vrouwelijke aanvragers is het laagst bij Natuurkunde (een bedroevende 11%), het programma met de hoogste honoreringskans.

Van de negen programma’s zijn er vier waarbij vrouwen een hoger honoreringspercentage hebben dan mannen: Exacte wetenschappen, Geesteswetenschappen, ‘Technologiestichting STW’ en ‘Gebiedsoverschreidend’. Bij de overige vijf programma’s, Scheikunde, Natuurkunde, Aard- en Levenswetenschappen, MaGW en ZonMW, halen mannen net betere resultaten. In geen der gebieden is het verschil zodanig dat – ermee rekening houdend dat meervoudige toetsen worden uitgevoerd – het verschil significant genoemd kan worden.

Oftewel: het discriminatievermoeden wordt in dit geval niet zo extreem sterk onderuit gehaald als in het klassieke voorbeeld uit Berkeley, maar wel sterk genoeg om te zien dat er niet geconcludeerd kan worden, op basis van deze data, dat er sprake is van discriminatie. NB: het tegendeel – er is geen sprake van discriminatie – kan ook niet geconcludeerd worden. De enige conclusie is dat uit de cijfers geen solide conclusie te trekken valt.

Tot zover de Simpsonparadox bij de NWO-cijfers. Nog enkele andere opmerkingen:

1) De cijfers per NWO-programma duiden naar mijn mening wel op een vorm van geïnstitutionaliseerde discriminatie: in geen van de negen onderzoeksprogramma’s vormen vrouwen de duidelijke meerderheid terwijl er in vier van de negen programma’s minstens twee keer zo veel mannen een aanvraag doen als vrouwen. Dit zijn nog steeds de bètarichtingen als scheikunde, natuurkunde, exacte wetenschappen en technologie (STW). Maar die vorm van discriminatie valt NWO niet (direct) aan te rekenen: dat is een maatschappelijk probleem dat op alle niveaus aangepakt moet worden. Het land heeft meer Ionicas Smeets, Ashas ten Broeke, Hannahs Fry en genderneutraal voedsel nodig, maar de rol die NWO daarin kan spelen is beperkt.

2) Ik zou nog terugkomen op de zin “The success rate was systematically lower for female applicants than for male applicants [14.9% vs. 17.7%; χ2(1) = 4.01, P = 0.045, Cramer’s V = 0.04]”. Bij deze. De chi-kwadraattoets is niet de meest geschikte toets om toe te passen bij 2×2 tabellen met frequenties. Dit omdat de chi-kwadraat een zogenaamde asymptotische toets is: hoe kleiner de frequenties in de tabel, hoe onnauwkeuriger de data. Een veelgebruikte correctie die die onnauwkeurigheid deels weghaalt, is die van Yates. Als je die toepast, verandert de p-waarde minimaal (want we werken hier met best grote frequenties): van 0,045 naar 0,051. Het verschil is minimaal, maar het springt wel nèt over de magische 5%. Als je met grote stelligheid een p-waarde vlak onder 5% als een duidelijk effect presenteert, zou je met dezelfde stelligheid een p-waarde daar vlak boven als “geen effect gevonden” moeten afdoen. Een ander alternatief – en beter omdat het geen asymptotische benadering is – is de exacte toets van Fisher. Deze geeft p = 0,046 (hoera! net aan de significante kant!). Er is eigenlijk geen enkele reden om de Fishertoets niet te gebruiken. Het enige nadeel is dat deze computationeel veel zwaarder is dan de chi-kwadraat toets. Dat was een terecht nadeel in de jaren ’20, toen Fisher die test ontwikkelde en Turing de moderne computer nog niet had uitgevonden. Anno 2015, kost de Fishertoets op deze data mijn computer 3 milliseconden.

3) Niet alleen is de p-waarde net wel/net niet significant, de effectgrootte is minimaal: Cramer’s V was gelijk aan 0,04. Als er al een verschil zou zijn tussen toelatingskansen van mannen en vrouwen, dan zou dit verschil erg klein zijn. Een klein beetje discriminatie is natuurlijk nog steeds ongewenst, maar de combinatie van minieme effectgrootte en nauwelijks significante p-waarde vereisen een veel voorzichtigere conclusie dan de conclusie “The data reported herein provide compelling evidence of gender bias in personal grant applications to obtain research funding.” van Van der Lee en Ellemers. (Hierbij moet wel opgemerkt worden dat de auteurs nog andere zaken bekeken dan alleen de 2×2 tabel die ik hier besproken heb. Maar ook met die extra gegevens is er geen statistische aanleiding tot grootspraak.)

4) De auteurs hebben de VENI-data van 2010, 2011 en 2012 bekeken. We zijn inmiddels alweer even verder. Zo kregen in 2015 14,9% van de vrouwen en ‘slechts’ 13,9% van de mannen de door hun gewenste beurs. Zou dit jaar bij de analyse betrokken zijn dan was – zelfs met de oppervlakkige chi-kwadraattoets die Van der Lee en Ellemers hebben toegepast – er niks overgebleven van de significante resultaten.

5) Los van de discussie over discriminatie laten de cijfers wel een schokkend iets zien: zowel voor mannen als voor vrouwen is het honoreringspercentage extreem laag. Dit houdt in dat er jaarlijks honderden wetenschappers zijn die enkele maanden van hun academisch leven besteden aan het schrijven van een voorstel dat uiteindelijk de prullenbak in gaat. Daar gaan dus duizenden en duizenden manuren èn vrouwuren aan verloren. Inmiddels wijst onderzoek na onderzoek uit dat de huidige manier van wetenschappelijke subsidies mogelijk meer nadelen dan voordelen heeft.

6) Deze hele discussie kent wat nare kanten – zo komen er wéér twee sociaal psychologen in het nieuws vanwege rammelend statistisch onderzoek – maar kan mogelijk ook tot goede ontwikkelingen leiden: zoals Daniël Lakens en Rolf Hut vandaag al in de Volkskrant schreven: het is een goede zaak dat NWO de aanvraagprocedure gender-neutraal maakt.

7) Als iemand weet waarom beide Volkskrantartikelen hierover (1 en 2) vergezeld gaan van een foto onze Koningin, dan hoor ik het graag. Ik zie de link tussen discriminatie, wetenschap en Máxima niet zo…

Deze blogpost is mede tot stand gekomen dankzij discussies met o.a. Daniël Lakens, Menno de Guisepe, enkele andere twittergebruikers en wat mailwisselingen met collega’s binnen en buiten Groningen. Mijn dank hiervoor.